Statoil has reported that it is possible, with the right organization and incentives, to drill the “perfect” well.

And when that happened it was time to redefine perfect.

In this case, perfect was defined as the most ambitious target time for drilling eight wells in Statoil’s Johan Sverdrup field.

While that discovery was one of the largest ever in the Norwegian North Sea, with oil prices around USD 50/bbl the Norwegian national oil company still needed to significantly reduce the cost of drilling to profitably develop the field.

The perfect well was one of the benchmarks set by a project that set out to redefine the working relationship between the operating company, the driller, and service providers to achieve “radical efficiency improvements from its own employees and from contractors,” according to a paper presented at the 2017 Offshore Technology Conference (OTC 27592).

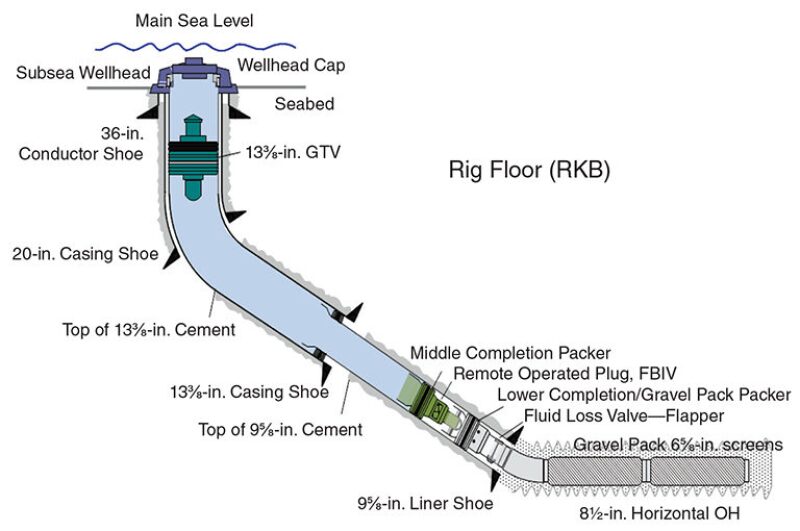

To lower costs, the well designs for Statoil’s Johan Sverdrup field focused on simplicity and standard parts. Source: OTC 27592.

During the planning process, the paper said there were workers from all the partners who said the goals were “too ambitious” and “far beyond reach,” the paper said.

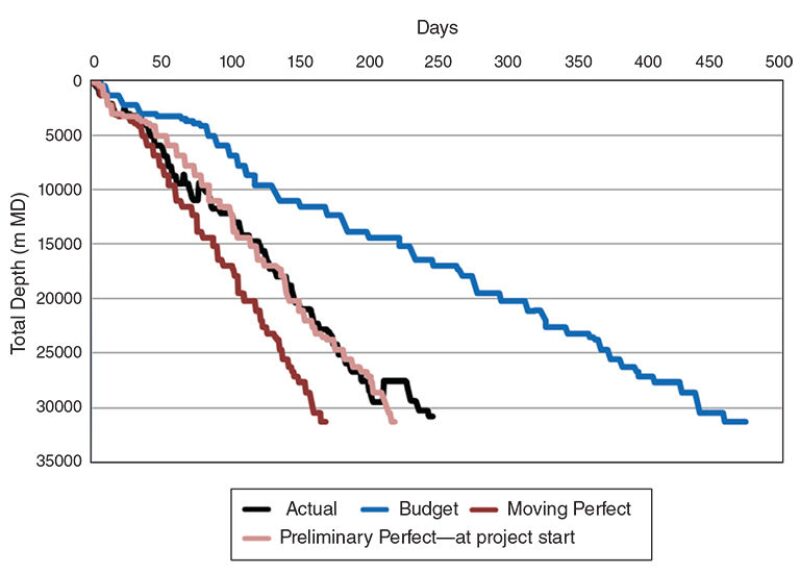

“Our actual delivery beat our initial perfect well,” said Jakup Oregaard, a drilling manager for Statoil, who presented the paper at OTC. So the company developed a new perfect line.

The actual drilling rate (black) far exceeded the pace in the budget (blue) and the perfect level (pink), matching the fastest pace on sections of comparable wells, leading to the creation of a new perfect line (brown). Source: OTC 27592.

Team Building

By rethinking the way drilling is organized and paid for, with an eye toward creating a team with shared goals that is highly motivated, Statoil was able to deliver “twice as many wells as we had budgeted for,” he said.

At the time it embarked on the experiment in 2015, all the parties involved had reason to embrace change.

Oil prices had dropped 50%, and were well below Statoil’s average break-even costs for offshore projects, and Johan Sverdrup was a critical one. The price crash led to mass offshore project delays and cancellations, leaving drillers and service companies hungry for work.

The perfect well was the simple tip of complex changes in the contractual and working relationship among Statoil and the two main service providers—Odjfell, the drilling contractor, and Baker Hughes, which coordinated other services.

The goal was to pay for work done rather than based on day rates. While the days of work still figured in, the bonus system was part of a compensation program designed to pay for “services actually delivered.”

Incentive payments are not new. Also, rather than payments awarded based on the work of the individual service provider, these required coordinated efforts among multiple companies.

“The offshore day rate is paid only when in operation,” the paper said. Services are compensated based on how much is accomplished. This could be payment based on meters drilled or cementing completed. In all cases, quality standards and safe operations remained essential.

Since workers play a critical role in change, the incentive payments were evenly split between companies and employees. Workers were reminded of their role with signs saying: “know your numbers.”

These contracts addressed common complaints from operators and the service companies. It de-emphasized day rates, which are often criticized by operators because working slower pays more. And it gave service providers, who complain they have limited influence because they are not involved in key decisions, particularly one made early on, a greater role.

The “integrated service contacts” were designed to ensure that the many service providers were coordinated under the leadership of the lead drilling and services contractors. The key people working offshore and onshore were represented each day in a morning meeting led by the drilling superintendent.

Experts from the project partners staffed a joint operations center in Stavanger with a video connection to offshore facilities. It allowed experts from the project partners to keep up with the work and quickly address problems as they came up.

For example, when drilling was halted by unstable wellbore that would require stopping and planning a sidetrack around the problem, they could “jump to the next well in situation where instability occurred, and not send valuable time troubleshooting with the drilling rig on location.”

About half the saving came from standardization and integration, he said. For example, well designs emphasized simplicity and standard elements.

The method is now being used to drill wells at Johan Sverdrup, and will be used when the fixed drilling platform is installed at the multi-platform development. At that point, the paper said “a challenge will then be to transfer the operating model over to a new organization.”

Related Multimedia

The beginning of production well drilling at the Johan Sverdrup field is recorded in this video showing top hole drilling. Source: Statoil.